I joined GDS in April, as a developer on GOV.UK. It was my first employer change in a while, and a deliberate switch from frontend to Rails development.

Here are some of my favourite things about working at GDS.

Development practices

Use of version control

At GDS we use git for version control, and treat git commits with as much importance as the code itself. Every commit should explain why a change was made – not just what has changed – and commits should be arranged into appropriate logical chunks.

We're not infallible, though. Mistakes do inevitably creep into commits and need to be rectified. Rather than adding another commit (‘fix linting error’) and then another commit (‘debugging Jenkins’), GDS encourages liberal use of git history rewriting.

The words ‘git rebase’ used to fill me with dread, and ‘force push’ always felt a bit naughty, but here I find myself rebasing and overwriting branches a dozen times a day. It’s worth noting that this is only applies to our branches – we do not edit the history on the master branch.

The result? Repository commit histories are a pleasure to browse.

This is important, as you never know who will be reading or editing your code next, and they should not need to come to you for additional context. This is compounded by the fact that no one team owns any particular codebase; teams are ephemeral and exist to fulfil a ‘mission’ in a fixed period of time. Teams might be created, disbanded or rotated any quarter.

You can read more about our processes in the git style guide.

Use of GitHub

At GDS, we code and make decisions in the open.

There are currently around 1,300 public repositories on GDS’s alphagov, and just a small handful of private repositories. Being open source is a prerequisite for launching a service that follows the GOV.UK Service Standard.

Site-wide technical decisions for GOV.UK are made in the open too, and can be suggested by any developer in the organisation in the form of a ‘request for comments’ (RFC). The RFCs repository describes the rationale behind a number of technical decisions, from what we call our environments to how many reviews an automated dependency update service should need.

GitHub workflows are nicely automated. When pull requests (PRs) are merged, a Jenkins job tags a release and stores it in GitHub, so we can see with relative ease what is included in each new deployment.

Equipment and cloud services

We have an accessibility lab kitted out with laptops running JAWS and Dragon NaturallySpeaking, and we have Chromebooks set up with profiles that emulate certain disabilities while you browse the web. The lab is available for anyone in GDS to use whenever they want to test something.

We use Macbook Pros and make use of cloud-based services, such as Google Docs, Gmail, Trello and Slack – not the kind of modern setup I was necessarily expecting from a government department!

Documentation

Documentation – or lack of – is one of the biggest grievances a developer will have with where they work. GDS documentation is generally very good, partly because there is a review mechanism built into the documentation itself.

Each piece of documentation has a 'last reviewed on' date and a 'review in' field. You can set the 'review in' value to, say, 6 months, and a bot will tell you on Slack when the time comes to review it, upon which you would update the 'last reviewed on' date.

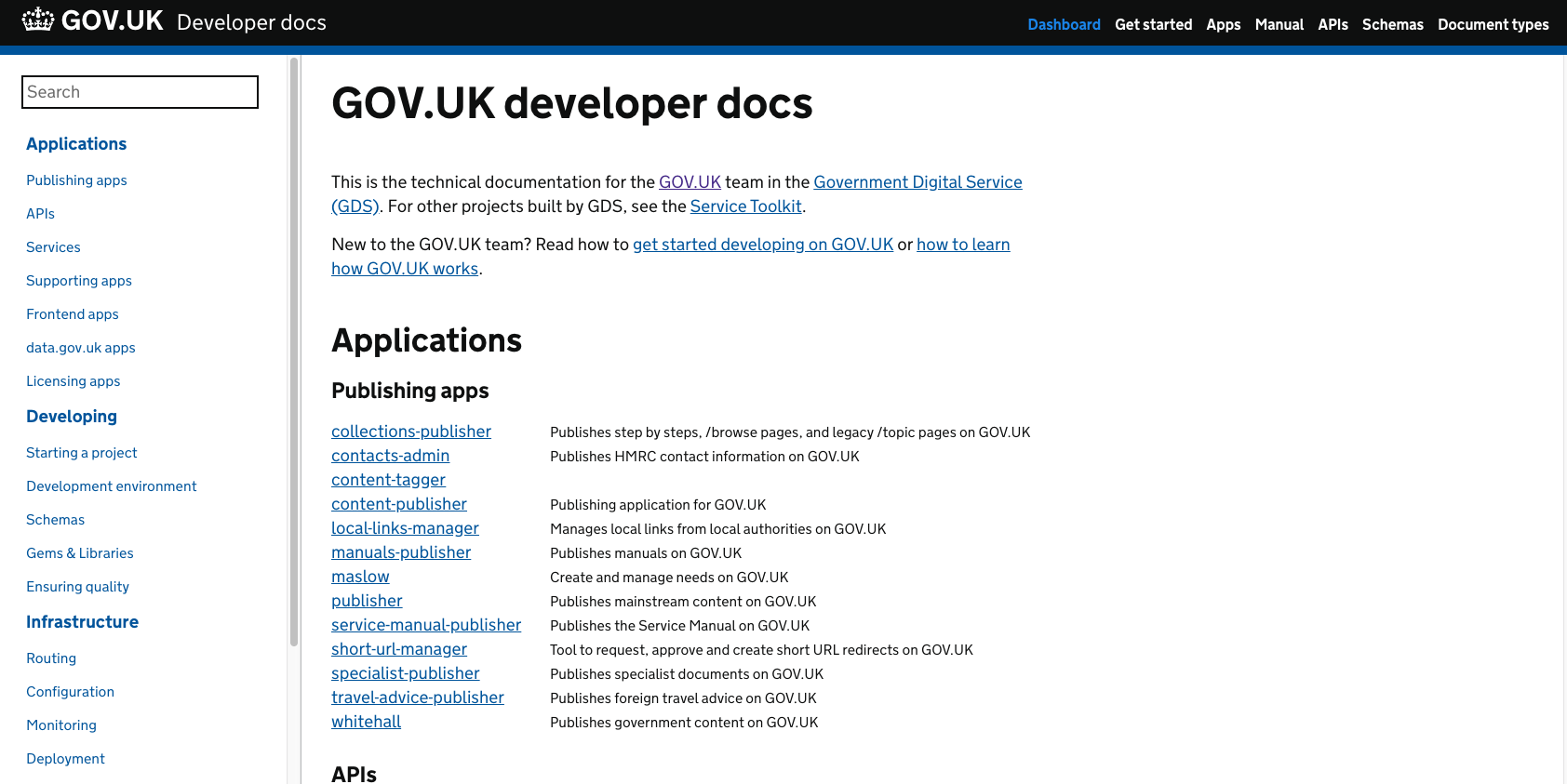

The developer documentation is easy to read and navigate as its look and feel is consistent with the main GOV.UK site. A consistent, accessibility-tested look and feel even applies to slides for internal presentations, which are written on a base template with the GDS house style.

Every page of documentation links back to its markdown source file in GitHub so that it can be easily edited if you spot a mistake. And if some documentation is particularly important, we have a willing team of technical writers to review its style and clarity.

Architecture

While GOV.UK looks like one big site, it's actually a number of user-facing applications that rely on backend microservices and a shared frontend Design System.

The microservice architecture means that code is split out into lots of smaller repositories, but this is hugely helped by the fact that things are named well. 'Search API' does what it says on the tin. 'Email Alert Frontend' – ditto. It offers an affordance to newcomers who can begin to put the overall architecture together relatively quickly.

Working with microservices raises some interesting challenges, particularly around co-ordinating releases. We've found ways to make microservices talk to each other locally and built confidence that it all works together by writing an end-to-end test suite.

We all get a chance to get hands on with this architecture, because once a quarter we're assigned '2nd line support' duty, which is essentially a devops rota. I really enjoyed my first week on 2nd line, and learned a lot about monitoring and debugging production systems.

Cultural practices

User focus

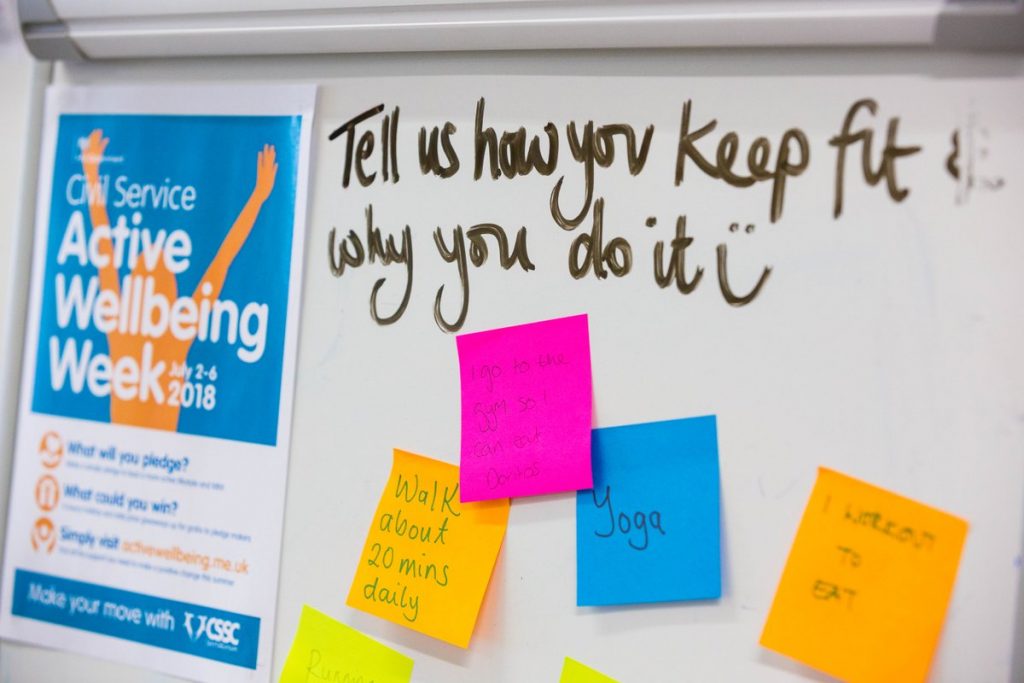

GDS encourages every employee to occasionally observe user research, whatever role they might have. As it says on posters around the building:

Everyone on the team should observe user research, regularly and often. It's the best way to make sure a service meets user needs.

Delivery teams (those that work on user-facing features) have a dedicated user researcher, whose primary focus is to plan and action user research sessions in the in-house observation lab, gathering feedback and testing assumptions. But the whole team gets involved in examining and interpreting the user lab analysis.

Sometimes, user research outcomes mean making difficult decisions, such as taking on technical debt, or abandoning a prototype that did not perform well. But it can also be very rewarding to see a change you've made improve the experience for the user in the lab, knowing that it’s making a positive difference to the wider population.

What we cannot test in a research lab, we try to glean from analytics. We have dedicated performance analysts who crunch the numbers and tell us which of our A/B tests provide the most effective user journey.

Roles

The roles here are slightly different to what I’m used to, and appear to be focused around team wellbeing and user needs.

GDS has visual designers who design components and layout, content designers who write copy and decide what text to put on a button or which content is more important to emphasise, and user researchers who arrange research labs and test the efficacy of designs. I'm used to designers being expected to do all 3 jobs, so it's a pleasant surprise to see so much investment being put into crafting a great user experience.

A 'tech lead' in other organisations tends to be a permanent position for a senior developer, with stakeholder management and line management duties. At GDS, it's a voluntary position any developer might be invited to take on when the teams are switched up every quarter. Being a tech lead does not necessarily involve line management, and line management does not necessarily require being a team lead. It means more developers can gain the experience of technical leadership without having to commit to a career change to do so.

As for developers, we're split into backend and frontend roles. My role of ‘developer’ is technically a backend one, but everyone has been very accommodating of my desire to be as full-stack as possible, and I've been able to contribute across the 2 communities.

Another interesting one: no testers. The responsibility is generally on the developer to build and test their own code (albeit with at least one review from another developer). This is usually sufficient when we're working on small iterations of existing features. New features are thoroughly tested by the frontend developer community and outside agencies.

Wellbeing

There is a strong support culture at GDS, including access to the Employee Assistance Programme for confidential mental health services such as counselling and therapy, and a Cabinet Office 'Listening Service' network of volunteers.

The workplace environment reinforces these with posters, dedicated Slack channels and one-off talks and events. Many teams are fans of fika, which is a chance to take a break from your screen and get to know your colleagues a little better.

GDS uses matrix style line management, and everyone I’ve met who is in a management position is aware of the concept of – and actively works to prevent – developer burnout. We are regularly reminded to take holidays and to try to use our full entitlement of leave.

Inclusive culture

I’m pleasantly surprised by the diversity of people that work at GDS, with a higher than industry average of female and BAME employees in technical roles.

The result is a culture where working in diverse teams is the norm and we can teach each other things we would not know otherwise (a ’Ramadan, Spirituality and Tech’ lunchtime talk was a recent highlight). This in turn helps our users, as more diverse teams lead to more inclusive designs. Outside of work, we can continue to socialise at volunteer-run communities such as chocolate tasting club, climbing club, and so on, with friendly people all round.

At retros, everyone is given time to speak, and we all genuinely commit to a no blame attitude. It's assumed that, whatever the situation, everyone has done the best they can. We follow the “retrospective prime directive” as outlined in Norman Kerth’s book, ‘Project Retrospectives: A Handbook for Team Review’:

Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand.

The openness of culture extends to code management. For example, nobody 'owns' any one part of the codebase. Everybody is expected to chip in, meaning knowledge gets spread around.

Summary

I’ve learned a lot in my time at GDS so far, and it’s been a lot of fun. We’ve made tangible improvements to the Brexit guidance for your business ‘finder’, and are now concentrating on improving the experience of creating and publishing step by step pages.

We’re always looking to hire good people so make sure you keep an eye on the GDS careers page.